South American football is about to die Between scandals and a low technical level a short reflection before River-Boca

We approach the conclusion of the epic of "the match of the century" that is a bit 'the slang that we used as children on the field, to describe an action even slightly above average when in the summer afternoons we played for hours and hours in a row, with matches from the rugbystical results, and then among friends in the winter months it was evoked every time a different game each defined, in fact, "of the century".

The first leg of the Copa Libertadores final between River Plate and Boca Juniors is behind us. It had been years since a game put Argentinian football so much in the spotlight, and in a sense it was an epitome of what is wrong with South American football in general; in fact, all our attention has focused more on the romantic narration and the emotional charge of the game, leaving aside the technical and tactical aspect, that were very rough according to most of the insiders. We have paid more attention to the colors of the Bombonera and "LA 12" than to the field, where a sport show not really exciting was staged, on the other end not paying too much attention to the fact that in a final of this kind of prestige the match was denied to the visiting fans; fact that, if transported in the European equivalent, the Champions League final, would have triggered a ruckus. To aggravate this situation, there are repeated scandals - ranging from corruption to pedophilia - that have invested South American football in almost all leagues and at all levels, including Libertadores.

However, we prefer to continue watching South American football with the nostalgic superficiality of football fans of bread and salami: the real sporting sentiment wrapped in a romantic and nostalgic patina ruined in European football by money. This is an understandable reasoning, but ultimately wrong, because South American football, like its countries is dirty, often rotten and there is nothing beautiful about it.

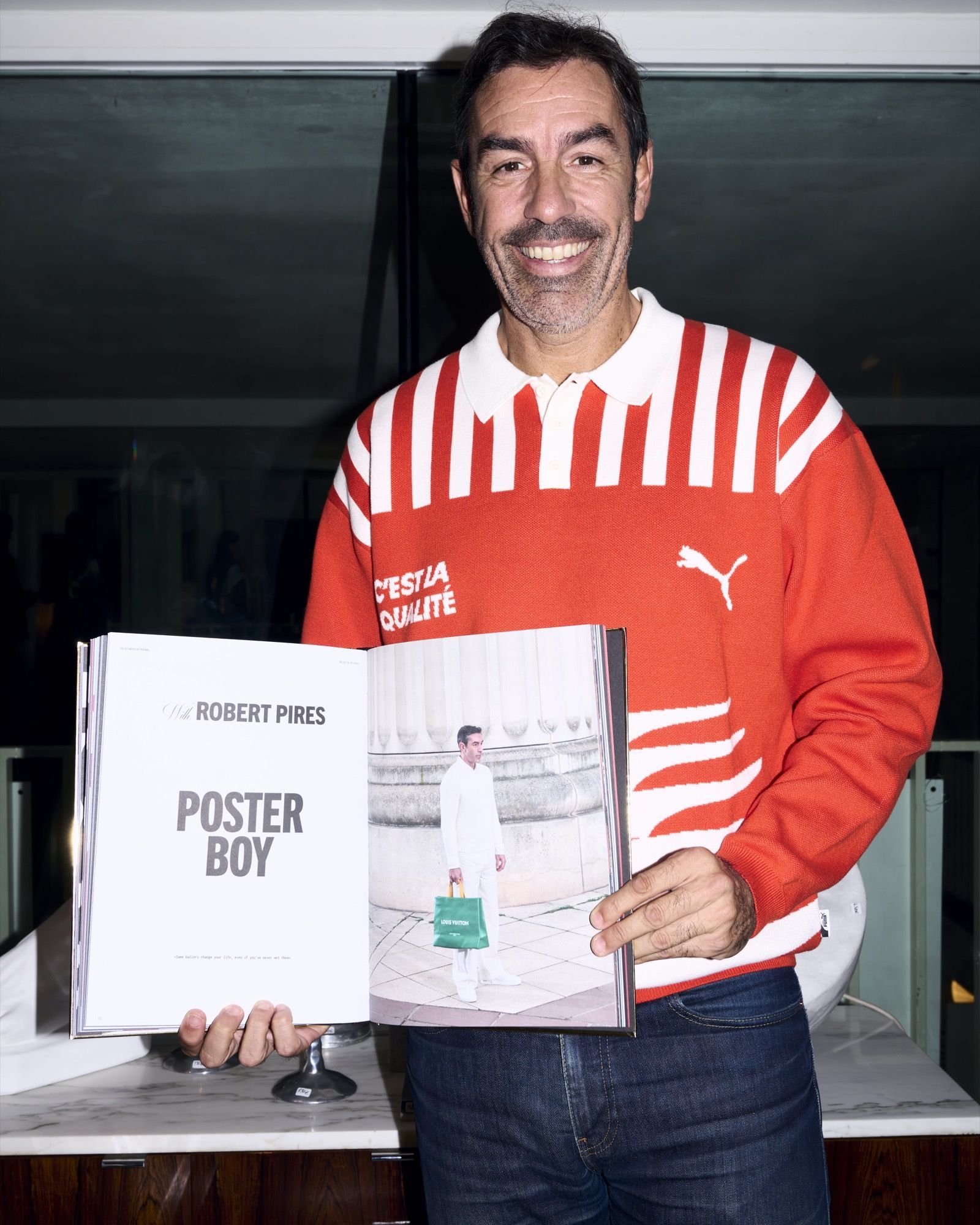

Boca-River

We’ll start from the epic first leg of the Final - the one played at Bombonera - and the technical decadence on the level of the game. When I said at the beginning that the first round of the Superclasico was defined "ugly" (let us not be fooled by the four goals) it was not just a hook to push you to read, it went just like that. They are there to prove the four goals: the first of Abila comes from a double resounding mistake of the goalkeeper of River, Armani, who is first to surprise on his pole from the violent conclusion of the Boca striker, rejecting the ball with a clumsy bagher, thus returning it to Abila, with no defender of the River that proves the contrast: the Argentinian striker kicks again on the goalie pole, managing to pierce the hands of the extreme defender from an even tighter angle.

The first goal of River comes instead from a passage without too many claims performed at the centre of the field by Scocco, which is transformed into filtering thanks to the awkward intervention of the defense that allows Pratto to score with a nice diagonal. The second goal of Boca brings the signature of Benedetto (1.75 m, not a great base elevation) that manages with a great turn of the head to anticipate its marker exactly in the middle of the area, intercepting a high and slow cross coming from a central punishment kicked for about forty meters. The "icing on the cake" is the fourth goal, that of the draw of River: another free-kick far from the area, another slow and sloping ball. This time it is even own goal, with Izquierdos that to anticipate all, throws it in his door with a sprawling.

These are not mistakes attributable to the extreme tension of the environment, the prestige of a so important final: it seems more a lack of technique and maturity in the choices, from the goalkeeper who rejects to the center of his area and gets pierced soon after on his pole, to the attacker that only in front of the goalkeeper tries a touch of outside completely meaningless; for the tactical aspect then we can not fail to mention both defenses, completely at the risk even on the most harmless balls. As if that were not enough then, the Chilean referee of the match, Roberto Tobar, in 2012 was involved in the "poker club scandal" and was also disqualified eight months: meeting with other Chilean referees to play poker, mail for the loser was to arbitrate minor games; a few years later we find a character like that to direct the most important final of the South American continent. Finally, just before the game, a police blitz took place in the River locker room, police who did not explain the reasons, seems to be looking for hidden bugs, given the disqualification of the River's coach, Marcelo Gallardo.

Romance vs reality

We are all madly in love with legendary stadiums like Bombonera or Maracanã, the epic and moving stories of redemption from the poverty of the brightest stars of the game, as well as the fans and their relationship with the teams, religious and transcendent reality. All this is undeniable, it really exists, and not being fascinated is absolutely impossible.

However, if we remove this veil of Maya from before our eyes, the real situation of South American football leaves us quite dumbfounded. Just look at the very recent world cup of Russia: Argentina and Brazil, loaded as always with huge expectations from the beginning, they stopped respectively in the second round and the quarter. The technical parable of the two main nationals of the South American block is exemplary. Each tournament faced in the last few years, but especially every world cup, should have been "the good one", the one in which Messi on one side and Neymar and co. on the other, they would finally return each side to the roof of the world. Every time the expectations clashed with reality, sometimes in a very brutal way, as for Mineirazo, in which the humiliation suffered by the Brazilian national against the German one has literally brought an entire country to its knees. The main problem, at least at the popular level (in the proper sense of people, of the fans), seems to be that these failures were faced almost by surprise, as if they were not predictable or affordable at all, but above all, as if they were literally divine will: nothing resolvable then: a simple knot and hitch in good fortune. To better understand this last concept we can focus on the tormented story of Messi with his National team. The Argentine people and the whole world have seen in him the natural heir of Maradona, given that the closest incarnation of the divine on earth for the Argentine people; consequently everyone expected that as Diego Armando did, also the Pulga would have dragged his National team to the victory of the World Cup, ignoring a whole series of objective factors that allowed Maradona's enterprise and that had little to do with his talent.

The failure of an entire movement, therefore, was almost ignored to focus on the alleged character limits of what is probably the strongest player in history, to which the responsibility for the various failures reclaimed over the years has been totally blamed. For example, the fact that all or almost the nations winners of the last few years have been due to the hand of their coaches has overshadowed - to the point that someone like Joachim Low, who lately is collecting several bad things, still sits on the bench of German national: Brazil, but above all Argentina, have lagged far behind this point of view. With the exceptions of Simeone or Pochettino, however two managers of "European" formation, the two main countries of the South American block, are struggling to produce technicians able to establish themselves at international level. Jorge Sampaoli after an incredible experience at the helm of Chile and a year at excellent levels with Seville has faced a total disaster with the Argentine national team, failing to win the confidence of the environment and players, almost ridiculing and erasing all his previous work.

An avalanche of scandals and arrests

This superficial romantic conception of South American football composed of spectacular choruses and choreographies that has supported it up until now and has concealed its darker and controversial aspects, is slowly fading, beginning to give away to real problems, increasingly evident and now undeniable. Months ago, almost simultaneously, in Brazil and Argentina a big scandal about pedophilia in the youth sectors of professional teams broke out, a dismal and humanly terrifying affair that had long been on the lips of many but never emerged for the great widespread silence in football environments.

In Argentina, violent organized fans is an integral part of football, the so-called barras bravas are real criminal groups that enjoy enormous consideration on the part of the social fabric to which they belong and are tied to both the club and the supporters (football players). and management, none excluded) that the same federation Argentina. In practice, they enjoy a total immunity in and around their stadium, being able to handle such dealerships, bagaring racket, extortion and so on; favor reciprocated by putting themselves at the service of politicians and men of power who need an armed arm; obviously from all this comes a guerrilla war between the different barras that almost every game causes deaths and injuries during, before or after the match on duty. Even in Brazil the situation is scandalous, especially as regards the situation of the clashes during the games, with news of maxi brawls, serious injuries and deaths that arrive every day here in Italy, often almost treated as folklore characteristic; not least Colombia, where the presence of drug cartels in football has been massive since the days of Escobàr and his (accepted) invitation to Maradona and Higuita to play a game in La Catedràl, his personal prison. Last but not least the Uruguay of Suarez and Cavani, who at the end of August faced a huge wiretapping scandal that led the federation to be a commissioner, with FIFA to take direct control of it. The same FIFA that is the subject of a scandal a month.

Gianni Infantino, the current president of FIFA, had found in the Uruguayan country one of the most fervent supporters for his election, after the scandal of 2015. And it is to be traced back to that scandal the arrest of three of the most important figures of the football politics of South America: Jose Maria Marin, former president of the Brazilian federation, Juan Angel Napout, even president of both the federation of Paraguay that of the whole Conmenbol (Confederacion sudamericana de Futbol) and Manuel Burga, president of the Peruvian federation.

The first two were recently sentenced to serve more than ten years in prison.

The conclusion that can be drawn is only one: the whole South American football system is rotten, from the roots up to the leaves, starting from the organized supporters up to the highest level institutional representatives.

All of this obviously can not have an important impact on played football, on its technical and tactical aspects, on the growth of young players and their ability to adapt to foreign championships as well as on a wild economic turn often dominated by corruption and bribes; not only for business related to young players' cards but also for international superstars.

The future

Returning to the personal mistakes of the players seem to show another aspect of the inadequacy or otherwise the difficulty of South American football; in the last few years apart from sensational exceptions, France, England but also Belgium have far surpassed Brazil and Argentina in terms of production of young champions, while it is increasingly emerging a difficulty of resounding adaptation of many South American talents sold as phenomena already made and by cumbersome comparisons, incapable for months (sometimes even years) to adapt to the pace necessary to compete in the highest European championships. Sign that the “schools” of the two countries have not been able to stand the comparison with the European countries mentioned above, which is evident at the moment when the world cup was won by France, Brazil came out against Belgium and the Argentina always against the cockerels. The man who symbolized France was Mbappè, a nineteen year old; the hopes of Brazil passed through Neymar's feet, twenty-seven years next February; those of Argentina for the left of Messi, thirty-one years old. There is a real generational problem and the cultivation of talents that seems far from its solution but that, perhaps, it is only at its beginning.

South American football has a wonderful history, made of pure passion and legendary champions that will remain forever in the history of sport. Precisely for his own sake it is therefore time to stop focusing all our attention only on this aspect of a football novel, from Federico Buffa's special, beginning to face the disastrous reality we have before our eyes.

South American football is slowly running out of oxygen, suffocated by enormous political corruption, the backwardness and radicalism of a hooligans culture that often gets confused with organized crime and not the obvious difficulties in being able to keep up with the technical and tactical evolution of the game. If we continue to focus our attention on that already saturated narrative universe that continues to warm the hearts of many and never on the terrible problems that are before our eyes, we risk being ourselves an important cause of the death of South American football.